The Melody of India

By Phelbé Pace

Music talk in Paris 18

“This experience will be outstanding for you, definitely”. A man and I are sitting in front of each other in a random bar located nearby the Music Academy of Paris 18th district. I am trying to describe to him the project I have been given the chance to lead for the upcoming summer: teaching English through music to the kids of the Tushita Foundation in Amber, Rajasthan. As I am listening to him, I know my summer experience starts here, with this man from Argentina, who speaks French perfectly and whose story echoes the one I’m about to have in India.

Many years ago, he came to France to become a choir director. In a country impregnated with restraint and rationality, he learnt – maybe unintentionally – the necessity of “cultural adaptation”. As a music professor, he also got progressively aware of how important flexibility was in teaching, particularly to a group of children. The kids he had been inspiriting so far had all been different: crippled and shy, novice and curious, or musically gifted and fascinated. Obviously, the transmission of his musical knowledge had never been based on selection. Now that I am facing him, I can almost read in his mind his personal belief: “everyone deserves music”. He is one of those dear defenders of citizens’ musical rights.

One hour passes and we talk about methodology. I’m asking him many questions to make sure I won’t be afraid when the time comes for me to reveal the wonders of music to Indian kids who don’t know me. He sings to show me a vocal exercise I could use with the children. Another man, sat behind us at the bar, looking very perky at 6:00pm, starts singing with him. “That man must be a music drunk” I assume, smiling.

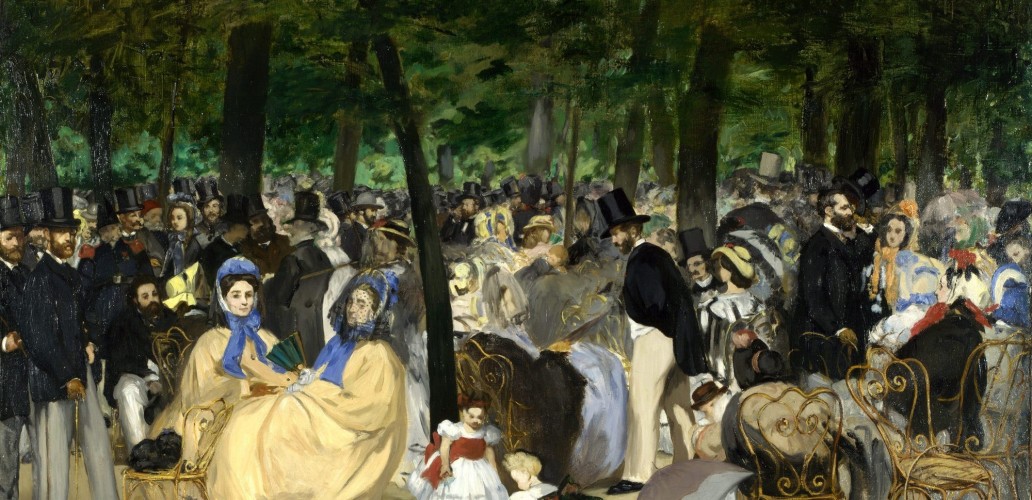

Before I go back home, enlightened and enriched by the precious discussion we had together, he invites me to enter the Music Academy. “There is something you must see”, he kindly tells me. I follow him in a corridor and go through a door on the left. Suddenly, everything is green around me and I feel the softness of the daylight on my skin: I am in the secret garden of the Academy. “Of course, there is a garden here” I think. “There is always a garden wherever people play music”.

Saturday afternoon fervor

This is my first Saturday at the Foundation. Cleo, Anthony and I – “the volunteers team” – have been introduced to the kids in the past days. I am wondering if two months will be enough to know all their names by heart but I already know it will surely be to remember their faces.

We are in Priyanka and Ruchika’s class, at the first floor of the Foundation. A carpet has been spread out on the floor for the kids to sit down. Guitaji is sitting on a chair, at the back of the room, holding court among the children with her natural elegance. Sonam comes in and brings two speakers from the kiddos’ classroom, into which Ruksar plugs her cellphone. The music begins. Three kids, free from any fear or shame, start to dance in the middle of an imaginary stage while their fellows vividly clap their hands. “I can’t believe I was in Paris one week ago” I realize, impressed by this demonstration of joy and spontaneity I had not expected them to offer me.

I am listening carefully to Indian music. I am intrigued by its energy, by the feeling of freedom it conveys, sustained by a fast and lively beat. Somehow, it carries an intrinsic opportunity for self-expression and communion. No one is afraid, no one is ashamed, no one wants to prove anything; everyone is just dancing on that cry of delight that Bollywood music wants to be.

Suddenly, dance enthusiasm comes to an end: the kids and the teachers have decided to sing together by a mutual and silent agreement. In one second, harmony takes over in the room through the genesis of a unified chant, unknown to me but more than familiar to them. The concert of their voices, perfectly matching with one another, clears up the role of music: building cohesion. No more cultural, linguistic or social distances to offset. Today, we are equally sharing the same amazing musical moment.

W.A. Mozart at the Foundation

“How would you call this instrument?”. Wide-eyed with astonishment, the children observe the clarinet I am showing to them in picture. They must have never seen that black instrument before, whose warm timbre started to be used from the 18th century for western orchestras. “Bansurî?” Jitendra suggests. He tried his luck by mentioning the name of the Northern Indian flute. “No, it’s not a flute”, I kindly say. “Do you want to hear the sound of it? It may help you make the difference between the two”. The kids accept my invitation for an unassuming music listening session by standing up and leaning on their elbows upon the classroom tables.

In the morning, I had thought about the piece of music I could bring with me to the Foundation to make the children discover the sound of a clarinet. It quickly occurred to me that the Adagio of the concerto in A Major of W.A. Mozart would be the best material I could use. Mozart was not only the composer who played a predominant role in the recognition of the clarinet in western operas and concertos; he was most of all a virtuoso whose genius left its graceful mark on western classical music. If the children had to learn musical references from the West, Mozart was a good name to start with.

I press “play” on my computer and turn the volume up on my antique speakers. The bright sound of the clarinet fills the room and immediately transports me. I stare at the kids, waiting for their reaction. Quiet and immobile, they look upward, in an attitude that reveals their interest and curiosity. They all seem to concentrate on the music, not only to note the characteristics of the clarinet’s timbre but also to distinguish it from the other instruments’, which are played in unison to escort the autumnal aria of the concerto. Bassoons, violins, French horns… They all sound so different from the mystical sitar or the rousing tablâs.

The soul of Mozart keeps on vibrating inside the classroom and slowly builds a bridge between the West and the East. I can see that the children have understood they were welcome to walk on it. Today, I am no more the only traveler.

Catching music around

The car is leaving the Foundation. Another day has passed. We are heading back to Jaipur where Maya, our “didi”, must be cooking a lovely dinner and where Lalsingh baya, the office protector, might be preparing a sweet and savoury lemon juice for us. We take rest in our thoughts as the beauty of India is delivered to us out of the windows. With difficulty, we make an effort to accept that the energy the kids have given us during the day is now gently waning at the end of the afternoon.

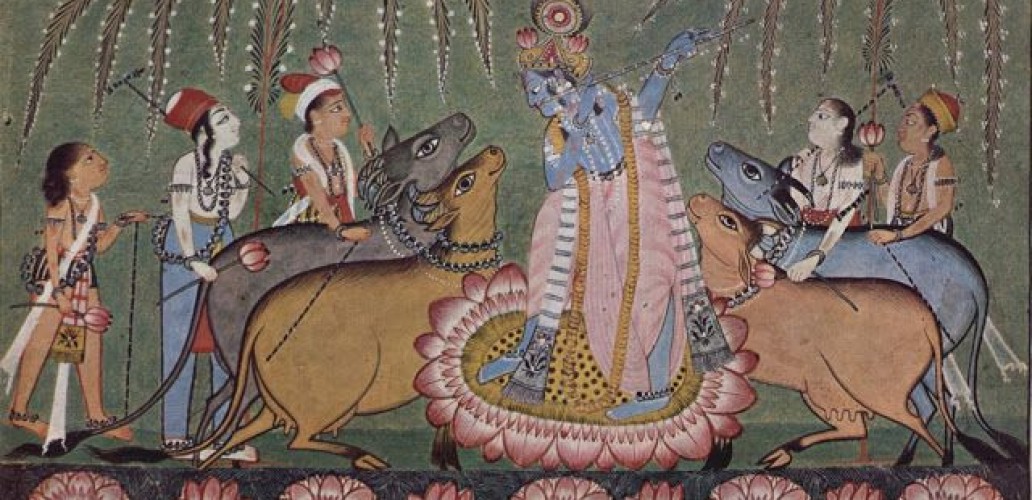

Gajju Bana understands we are ready for a sweet and succinct evasion. As he wants to content our needs – as usual – he rolls out his biggest card: a song of A.R. Rahman, the contemporary virtuoso of India, extracted from one of the most classic Bollywood movies, Jodhaa Akbar. The film is a love story, taking place in the 16th century, between the Muslim Emperor Akbar and the daughter of the Raja of Amber, the Hindu princess Jodhaa. The contemplation of the Amber Fort from the car makes this musical allusion to the movie more than appropriate.

Our benevolent Hindi teacher, Veenaji, tells us that “Khwaja mere Khwaja” – the title of the song – means “God, my God”. As a matter of fact, the outside looks divine: colors are shining, faces are smiling, cars are honking while we keep on rolling. Meanwhile, the soft and intense voices of Indian singers adorn the world at which we gaze with ardor and spirituality. I get out my camera from my bag to capture this moment. The picture is eventually taken and the instant gets engraved in my memory.

Ending in an authentic cadence

Cleo, Anthony and I did the same route every day from the office of Jaipur to the Foundation of Amber for two months until we had to come back home. That day, that final day, we left a part of us at the Foundation when Veenaji, Gajju Bana, the teachers and the kids waved at us to say goodbye. As we were moving away from a place that had sheltered us for a whole summer, we allowed ourselves to cry, deeply and silently, when no one could see us anymore. Still, out of the windows of the car, India was there to wipe our tears away, as we were attempting to regain consciousness, little by little. I remember I wished we had some music to play to soothe our sadness away. But the musicality of India quickly captivated me. People were talking, working, eating, laughing, yelling, sleeping, and bargaining in the streets. We could hear no noise from the car but after two months, the rhythm and the tone of Indian alleys were distinctively resonating in my mind.

Today, although I am far away, the music of Rajasthan and of the Tushita Foundation is still playing in my heart.

Music is inside of us; Music is everywhere.